Where Are All the Passive Houses?

Passive houses are energy efficient, comfortable, and relatively inexpensive, so why aren’t we rushing to build them?

I know this may come as a shock, but I have an ax to grind.

Buildings use 75% of the electricity we generate in this country, making them a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. We could be doing a lot more to lower that number, but we’re not.

There are many ways you can reduce the energy consumption of buildings, and one very effective way of doing so is through passive solar design, a smart way of designing buildings that works with (not against) the sun to optimize the storage and distribution of the heat it generates. Passive House (or Passivhaus, if you want to use the original German) is the building standard that uses the latest techniques in building science best practices, including passive solar design, to certify super energy efficient buildings.

I think Passive House design is really cool and makes a lot of sense, so I was surprised to discover that we just don’t build a lot of them in the US, especially not in the South. In this post, I want to explore why that is and how we can fix it.

American buildings use a sh*t ton of electricity

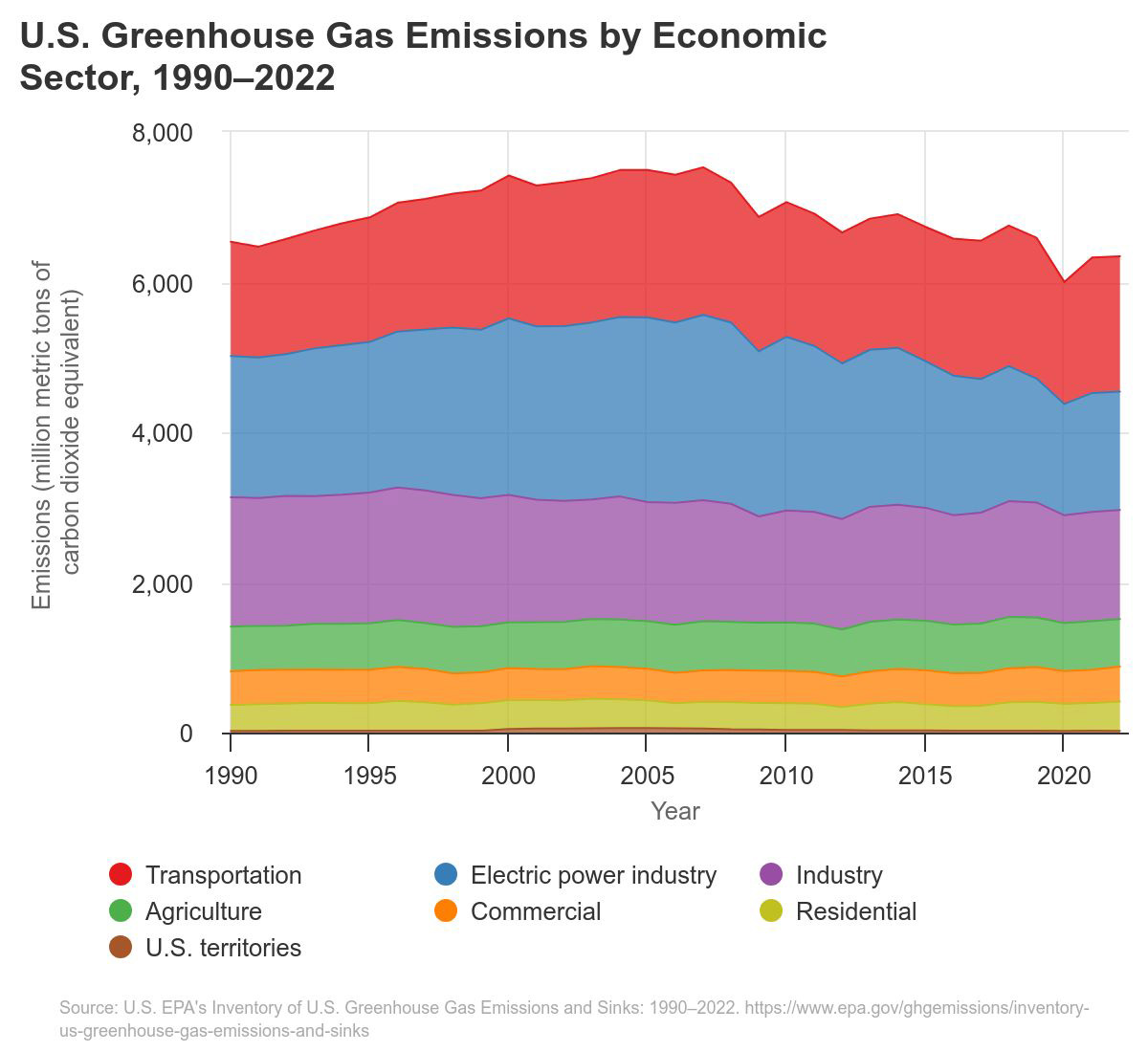

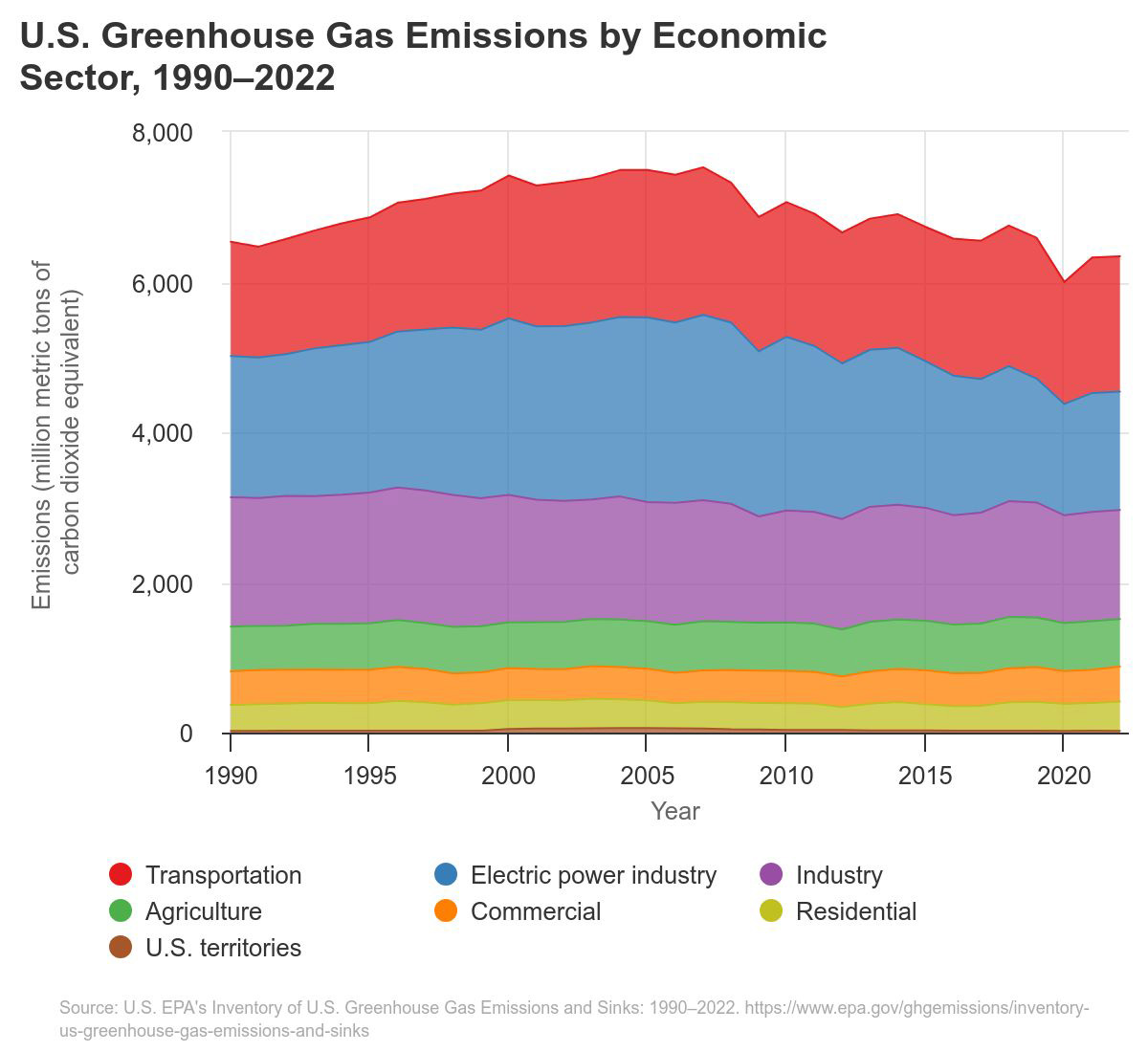

Building electricity use gets accounted for under the “Residential & Commercial” economic sector in the EPA’s Inventory of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, which was responsible for 31% of greenhouse gas emissions in the US in 2022.

Both residential and commercial buildings consume electricity in a number of different ways. To wit:

- Air conditioning (depending on the climate)

- Lighting

- Ventilation

- Heating (depending on the type of furnace)

- Appliances

Obviously some houses don’t have AC and others don’t use an electric furnace, but most appliances are electric (yes, that goes for stoves, too). We are also using way more home appliances than we were, say, 20 or 30 years ago.

So far I’ve talked mostly about residential buildings, but the real elephant in the room here is commercial buildings. To see what I mean, kindly consider the chart below from the EPA.

This stacked area chart shows GHG emissions from the Commercial economic sector as being roughly twice that of emissions from the Residential sector. This isn’t really surprising, but it’s important to keep in the back of your mind as we move on to actually talking about passive houses, as the name can sound like a misnomer.

Passive houses don’t use a sh*t ton of electricity

Good news everyone! Passive houses are specifically designed to not use a lot of electricity, and they do not only work for single family homes.

In fact, there are many commercial buildings around the world built according to the Passive House standard. I don’t know if its claim of being the biggest Passive House certified office building in the world holds up to scrutiny or not, but at least one of the biggest Passive House office buildings in the US is the Winthrop Center in Boston. Clocking in at 812,000 square feet distributed across 53 stories, this tower is one of the tallest buildings in the Boston skyline.

According to Architectural Record, a regular office building in Boston will use 150% more energy than the Winthrop Center building, and even a certified LEED Platinum building (what many people perceive as the gold standard of energy efficiency in buildings) will use 60% more than this Passive House office building. Oh, and Winthrop Building also has 30-50% more fresh air indoors than existing buildings, making it healthier as well.

But wouldn’t something like this cost an arm and a leg? Hold your horses, partner.

The cost of building passive houses varies by location—the climate, cost of building materials, cost of labor, cost of land, etc. will vary significantly for buildings in, say, Seattle, WA versus Birmingham, AL. That being said, passive houses do not cost significantly more to build than conventional buildings, especially when it comes to commercial buildings. If there is a difference, we’re talking a 1-4% premium.

In fact, the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA), an affordable housing agency, actually saved money by building a senior housing project according to Passive House standards in 2018. The Morningside Crossing apartment building in Pittsburgh is 68,212 square feet and had a lower cost per square foot to build compared to using conventional building standards. That doesn’t include savings from energy costs over the years, which would otherwise be significant.

The government can incentivize construction of passive houses

If cities and states in the South really want to get serious about lowering carbon emissions from buildings (and let’s be honest, it’s probably cities that care about this, not states), they will create financial incentives to build Passive House certified buildings.

Pennsylvania had the highest rate of Passive House construction when the PHFA decided to tie Passive House certification to eligibility for federal low-income housing tax credits. In Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center offered awards of up to $4,000 per unit for eight new multi-family affordable housing builds, producing real-world buildings that could validate the cost of building passive houses in Massachusetts (a less than 3% premium compared to conventional buildings). This in turn inspired other incentive programs, spurring the development of more passive houses.

On a city level, New York incentivized Passive House construction and retrofits with the passage of Local Law 97, part of the city’s Green New Deal package that requires most large buildings in the city to meet certain energy efficiency standards and reduce GHG emissions. The building standards criteria get stricter in 2030, with the ultimate goal of eliminating emissions from buildings in New York City by 2050.

Imagine what could happen if cities and states in the South adopted similar playbooks. We could even learn from both incentive structures and take a carrot-and-stick approach—offering tax credits for building new passive houses and charging penalties for new buildings of a certain minimum size that don’t live up to Passive House standards.

The South is way hotter than the Northeast, but that doesn’t have to hold us back

One last thought here before I wrap up.

Back in March, I had the opportunity to tour the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design at Georgia Tech with a group of folks from our local Work on Climate group. The Kendeda Building is not (as far as I know) Passive House certified, but it is Living Building Challenge certified. It’s currently one of 28 buildings like it in the world and the only one in the South—most of the others are on the West Coast.

At first, architects weren’t sure if it was possible to build something as energy efficient as the Kendeda Building in Georgia’s hot, humid climate, but they managed to pull it off. Today, the building is regenerative, meaning it generates more electricity than it uses in a year, and it features no conventional HVAC system. Hot damn!

Instead, thanks to the building’s passive solar design, it remains a comfortable 74° F year-round. The building’s gutter system channels rain into underground cisterns where it can be treated to be drinkable, and all the toilets in the building are composting toilets (and you would never know—it doesn’t smell). The building was also constructed out of sustainable, local materials, including industrial timber, which I might just have to write about someday.

The Kendeda Building was built for slightly more than the cost of a conventional building (unfortunately I don’t have the numbers), but it actually makes money for Georgia Tech since it can sell the excess energy it generates back to the grid.

Point being, we can do this kind of thing here. It doesn’t just have to be states like Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York leading the charge on green building (although, good job y’all). We just need to start pulling the right levers.